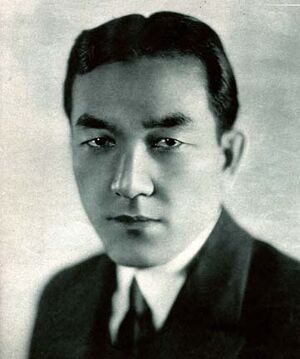

Sessue Hayakawa|早川 雪洲|Hayakawa Sesshū, June 10, 1886 - November 23, 1973 was a Japanese actor who starred in both Japanese and American films. Hayakawa was the first and one of the few Asian actors to find stardom in the United States as well as Europe[1], during his time he was as well known as Charlie Chaplin and Douglas Fairbanks.[2] He was one of the highest paid stars of his time; making $5,000 a week in 1915, and $2 million a year via his own production company during the 1920s.[3]He starred in over 80 movies and has two films in the U.S. National Film Registry.[4] His international stardom transitioned both silent films and talkies. [5]

Of his English language films, Hayakawa is probably best known for his role as Colonel Saito in the film The Bridge on the River Kwai, for which he received a nomination for Best Supporting Actor in 1957. In addition to his acting career Hayakawa was also a film and theatre producer, author, martial artist, and an ordained Zen master.[6]

Early life[]

Hayakawa was born Kintaro Hayakawa (早川金太郎, Hayakawa Kintarō) in the Nanaura Village, of Chikura Town, of Minamibosō City, in the Chiba Prefecture, Japan on June 10, 1886, the second eldest son of the provincial governor.[7]

From early on Hayakawa was groomed for a career as a naval officer. However at the age of 17, he took a schoolmate's dare to swim to the bottom of a lagoon (he grew up in a shellfish diving community) and ruptured his eardrum. He had been studying at the Naval Academy in Etajima but his record of perfect health was now shattered and he failed the navy's rigorous physical. His formerly proud father was now ashamed and embarrassed of his son. Their relationship became strained.[8]

The strained relationship drove the Hayakawa to attempt seppuku (ritual suicide). One quiet night after dinner Hayakawa entered a garden shed on his parents' property, locked his favorite dog outside and spread a white sheet on the ground. To uphold his family's samurai tradition, Hayakawa stabbed himself in the abdomen more than 30 times.[9] The dog's barking alerted Hayakawa's family and his father smashed through the shed door with an axe in time to save his son.[10]

After he recovered from the suicide attempt Hayakawa enrolled in the University of Chicago to study political economics.Hayakawa enrolled at the University of Chicago to study political economics. His family had decided that if he could not be a naval officer, he would become a banker. Three years after arriving in the US, Hayakawa briefly returned home after his father's passing. His older brother pleaded with him to stay in Japan however Hayakawa saw no future for himself there and returned to the US.[11]

Career Beginnings[]

Hayakawa was on vacation in Los Angeles when he wandered into a Japanese Playhouse in Little Tokyo. He soon was fascinated with acting and performing plays. It was around this time he first assumed the name Sessue Hayakawa.[12]

One of the productions Hayakawa performed in was called The Typhoon. The well known film producer Thomas Ince saw the production and offered to turn it into a silent movie using the original cast. Anxious to return to his studies at the University of Chicago, Hayakawa decided to try and dissaude Ince by requesting the absurdly high fee of $500 a week. Ince agreed to pay it.[13]

The Typhoon was filmed in 1914, and was an instant hit. Hayakawa made two more films with Ince, The Wrath of the Gods co starring his new wife Tsuru Aoki, and The Sacrifice. With his rising stardom Hayakawa soon was offered a contract by Jesse L. Lasky. He signed on making him part of Famous Players-Lasky (now Paramount Pictures).[14]

Stardom[]

Hayakawa second film for Famous Players Lasky was The Cheat, directed by Cecil B. DeMille. The Cheat co starring Fannie Ward, was a huge success, making Hayakawa a romantic idol to the female movie going public.[15] With his popularity Hayakawa's salary soared to over $5,000 a week in 1915. In 1917 he built his residence, a castle styled mansion, on the corner of Franklin Avenue and Argyle Street in Hollywood, which became a landmark until being torn down in 1956. [16]

Following the success of The Cheat Hayakawa became a top leading man for romantic dramas in the 1910s and early 1920s.[17] After these roles he switched to Westerns and Action films.[18]

After years of extensive typecasting at Famous Players, Hayakawa decided to form his own production company. He borrowed $1 million from a former classmate at the University of Chicago and formed Haworth Pictures Corporation in 1918.[19] Over the next three years he pumped out 23 films and netted $2 million a year.[20] Hayakawa controlled the content. He produced, starred in, and contributed to the design, writing, editing, and directing of the films. His films influenced the way the American public viewed Asians.[21]

In 1918 Hayakawa personally chose the highly popular American serial actress Marin Sais to appear opposite him in a series of films, the first being the 1918 racial drama The City of Dim Faces followed by His Birthright, which also starred his wife. Hayakawa's collaboration with Sais ended with the 1919 film Bonds of Honor.

In 1919 Hayakawa made what is generally considered one of his best films, The Dragon Painter. During this period Hayakawa was at his Hollywood peak. He was one of thie highest paid stars of the era, making $2 million a year through his production company throughout the 1920s.[22] His fame rivaled that of Douglas Fairbanks, Charlie Chaplin, and in many ways he can be seen as a precursor to Rudolph Valentino.[23]

Hayakawa's wealth and extravagance was legendary. He drove a gold plated Pierce-Arrow. He entertained lavishly in his 'Castle' which was known as the scene of some of Hollywood's wildest parties. Shortly before Prohibition took effect in 1920, he bought a carload of booze. Hayakawa once claimed that he owed his social success to his liquor supply.[24] During this time, in the course of one night he gambled away $1 million in Monte Carlo, shrugging off the loss while another Japanese gambler who lost a fortune committed suicide.[25]

Stardom outside of the United States[]

A bad business deal forced Hayakawa to leave Hollywood in 1921. The next 15 years saw him performing in New York, France, England and Japan. In 1924 he made The Great Prince Chan and The Story of Su in London.[26]

In 1925 he wrote a novel, The Bandit Prince, and turned it into a short play. In 1930 he performed in a one-act play written especially for him, Samurai, for King George V of Great Britain and Queen Mary. He also became very popular in France thanks to the prevailing French fascination with anything Asian. In 1930 Hayakawa returned to Japan and produced a Japanese-language stage version of The Three Musketeers.[27]

Later career[]

In the 1930s his career began to suffer from the rise of talkies, as well as a growing Anti-Japanese sentiment. Hollywood deemed his gifts unsuitable for the new talkies. Hayakawa's sound film debut came in 1931 in Daughter of the Dragon, starring opposite fellow Asian performer Anna May Wong.[28]

In 1937 Hayakawa went to France to act in Yoshiwara and found himself trapped by the German occupation. He was separated from his family during this time.[29]

Hayakawa made few movies during these years, but supported him by selling watercolors. He joined the French Resistance and helped Allied flyers during the war. [30]In 1949, Humphrey Bogart's production company tracked Hayakawa down and offered him a role in Tokyo Joe. Before issuing a work permit, the American Consulate investigated Hayakawa's activities during the war. They found that he had in no way contributed to the German war effort. Hayakawa followed Tokyo Joe with Three Came Home, in which he played a real-life POW camp commander Lieutenant-Colonel Suga, before returning to France.[31]

His post-war screen persona became fixed as the honorable villain, perhaps best exemplified in his role as Colonel Saito in the film The Bridge on the River Kwai, which won the 1957 Academy Award for Best Picture. Hayakawa was nominated for Best Supporting Actor but lost to Red Buttons. He was also nominated for a Golden Globe for the role. He called this role the highlight of his career.[32]

After that film Hayakawa in essence retired from acting. Throughout the rest of his life he performed on a handful of television shows and a few movies. His final film appearance was in The Daydreamer in 1966.[33]

Other Works[]

Hayakawa had created his own production company in 1918. During that period he produced, directed, contributed to the design, writing, of editing his films.[34] He wrote several plays, painted watercolors, performed martial arts, and invested wisely.[35]

In 1961 he became a Zen master as well as a private acting coach.[36] He wrote an autobiography, Zen Showed me the Way.[37]

Acting Style[]

During the height of his popularity critics of the day hailed Hayakawa's Zen-influenced acting style. Hayakawa sought to bring muga, or the "absence of doing," to his performances, in direct contrast to the then-popular studied poses and broad gestures. He was one of the first stars to do so; Mary Pickford being the other.[38]

Racisim and Racial Barriers[]

Hayakawa was in a unique position due to his ethnicity and fame in the English world. Due to Anti-miscegenation laws that existed at the time Hayakawa would be unable to become a citizen or marry someone of another race. In 1930 the Hays Code came into effect which forbid portrayls of miscegenation in film. Due to the practice of yellowface this meant that unless Hayakawa played oppiosite an authentic Asian actress; he would not be able to portray a romance with her.

Throughout his career the United States dealt with yellow peril which affected Americans perceptions of Asians. This left Hayakawa to constantly be typecast as a villain or forbidden lover; and unable to play parts that would be given to fellow white actors such as Douglas Fairbanks.[39]

Hayakawa can be seen as a precursor to Rudolph Valentino. Both were foreign born, both were typecast as exotic or forbidden lovers, and both were wildly popular during their time. Hayakawa also inadvertently helped Rudolph Valentino's rise to stardom. His contract with Famous Players expired in May 1918, but the studio still asked him to star in The Sheik. Hayakawa turned down the picture in favor of starting his own company; most likely not happy with another 'forbidden villain lover' role. With influence from June Mathis, the role went to the barely known Valentino, which turned him into an icon.[40]

Reception in Japan[]

Hayakawa's early films were not popular in Japan most likely due to the fact that Hollywood played up his Japaneseness, at a time that Japan was trying to become more American.[41]

Some Japanese felt his American success represented turning his back on his nation. His later films were also not popular, ironically enough because he was now seen as 'too Americanized' during a time of 'Nationalism'.[42]

Reception in United States[]

In more than 20 films for Famous Players Hayakawa was typecast as either the villain, or the exotic lover who in the end would turn his lover over to the proper man of her race.[43]

This typecasting was the reason Hayakawa set up his own production company in 1918 around the height of his US fame. At that time he stated he wanted to be shown "as he really is and not as fiction paints him." As for his prior roles, he said, "they are false and give people a wrong idea of us (Asians)."

Hayakawa desperatly sought to show a more balanced and fair portrait of Asians. In 1949 he stated, “My one ambition is to play a hero.” In his autobiography he observed, “All my life has been a journey. But my journey differs from the journeys of most men.”

Personal life[]

On May 1, 1914 Hayakawa married fellow Japanese actress Tsuru Aoki. She would star in quite a few of his movies alongside him.[44] She died in 1961 at which time Hayakawa moved back to Japan and became a Zen master.

In Europe the couple adopted a boy, Yukio who became an engineer. They also adopted 2 daughters: Yoshiko an actress, and Fujiko a dancer.

Hayakawa was known for his discipline and martial arts skills. While in University he played quarterback for the football team. He was once penalized for using jujitsu to bring down a rival player.[45]

While filming The Jaguar's Claws, in the Mojave Desert, Hayakawa played a Mexican bandit, and the film required 500 cowboys as extras. On the first night of filming, the extras drank all night and well into the next day. No work was being done, so Hayakawa challenged the group to a fight. Two men stepped forward. Hayakawa said of the incident, "The first one struck out at me. I seized his arm and sent him flying on his face along the rough ground. The second attempted to grapple and I was forced to flip him over my head and let him fall on his neck. The fall knocked him unconscious." Hayakawa then disarmed yet another cowboy. The extras returned to work, amused by the way the small man manhandled the big bruising cowboys.[46]

Death[]

Sessue Hayakawa had retired from filming in 1966. After his wife's death he had returned to Japan where he became a Zen master and a drama coach. He died in Tokyo on November 23, 1973 from a blood clot in the brain; complicated by pnemonia.[47] He was buried in the Chokeiji Temple Cemetery in Toyama, Japan.[48]

Legacy[]

To date Hayakawa is the only Asian to obtain romantic icon status in the US. His work lives on in various forms. Many of his films are lost. However most of his later films including The Geisha Boy, Tokyo Joe, Three Came Home, and The Bridge on the River Kwai are available on DVD.

For his contribution to the motion picture industry, Sessue Hayakawa was awarded a star on the legendary Hollywood Walk of Fame at 1645 Vine Street, in Hollywood, California.

In 1989 a musical based on his life, Sessue, played in Tokyo.

In September 2007 the Museum of Modern Art held a retrospective on Hayakawa's work titled: "Sessue Hayakawa: East and West, When the Twain Met"[49]

Filmography[]

- Main article: Sessue Hayakawa filmography

References[]

References[]

- ↑ http://www.silentera.com/people/actors/Hayakawa-Sessue.html

- ↑ http://www.dukeupress.edu/books.php3?isbn=978-0-8223-3969-4

- ↑ http://goldsea.com/Personalities/Hayakawas/hayakawas.html

- ↑ http://www.dukeupress.edu/books.php3?isbn=978-0-8223-3969-4

- ↑ http://www.dukeupress.edu/books.php3?isbn=978-0-8223-3969-4

- ↑ http://www.dukeupress.edu/books.php3?isbn=978-0-8223-3969-4

- ↑ http://www.silentera.com/people/actors/Hayakawa-Sessue.html

- ↑ http://goldsea.com/Personalities/Hayakawas/hayakawas.html

- ↑ http://goldsea.com/Personalities/Hayakawas/hayakawas.html

- ↑ http://goldsea.com/Personalities/Hayakawas/hayakawas.html

- ↑ http://goldsea.com/Personalities/Hayakawas/hayakawas.html

- ↑ http://goldsea.com/Personalities/Hayakawas/hayakawas.html

- ↑ http://goldsea.com/Personalities/Hayakawas/hayakawas.html

- ↑ http://www.silentera.com/people/actors/Hayakawa-Sessue.html

- ↑ http://www.silentera.com/people/actors/Hayakawa-Sessue.html

- ↑ http://goldsea.com/Personalities2/Hayakawas/hayakawas2.html

- ↑ http://www.silentera.com/people/actors/Hayakawa-Sessue.html

- ↑ http://www.silentera.com/people/actors/Hayakawa-Sessue.html

- ↑ http://www.silentera.com/people/actors/Hayakawa-Sessue.html

- ↑ http://goldsea.com/Personalities2/Hayakawas/hayakawas2.html

- ↑ http://goldsea.com/Personalities2/Hayakawas/hayakawas2.html

- ↑ http://goldsea.com/Personalities2/Hayakawas/hayakawas3.html

- ↑ http://goldsea.com/Personalities2/Hayakawas/hayakawas3.html

- ↑ http://goldsea.com/Personalities2/Hayakawas/hayakawas3.html

- ↑ and adopted two girls and one boy.

- ↑ http://goldsea.com/Personalities2/Hayakawas/hayakawas3.html

- ↑ http://goldsea.com/Personalities2/Hayakawas/hayakawas3.html

- ↑ http://goldsea.com/Personalities2/Hayakawas/hayakawas3.html

- ↑ http://goldsea.com/Personalities2/Hayakawas/hayakawas3.html

- ↑ http://goldsea.com/Personalities2/Hayakawas/hayakawas3.html

- ↑ http://goldsea.com/Personalities2/Hayakawas/hayakawas3.html

- ↑ http://goldsea.com/Personalities2/Hayakawas/hayakawas3.html

- ↑ http://goldsea.com/Personalities2/Hayakawas/hayakawas3.html

- ↑ http://goldsea.com/Personalities2/Hayakawas/hayakawas2.html

- ↑ http://goldsea.com/Personalities2/Hayakawas/hayakawas2.html

- ↑ http://www.silentera.com/people/actors/Hayakawa-Sessue.html

- ↑ http://goldsea.com/Personalities2/Hayakawas/hayakawas2.html

- ↑ http://goldsea.com/Personalities2/Hayakawas/hayakawas2.html

- ↑ http://goldsea.com/Personalities2/Hayakawas/hayakawas3.html

- ↑ http://goldsea.com/Personalities2/Hayakawas/hayakawas3.html

- ↑ https://archive.is/20121219015029/search.japantimes.co.jp/cgi-bin/fb20070812dr.html

- ↑ https://archive.is/20121219015029/search.japantimes.co.jp/cgi-bin/fb20070812dr.html

- ↑ https://archive.is/20121219015029/search.japantimes.co.jp/cgi-bin/fb20070812dr.html

- ↑ http://goldsea.com/Personalities2/Hayakawas/hayakawas3.html

- ↑ http://goldsea.com/Personalities/Hayakawas/hayakawas.html

- ↑ http://goldsea.com/Personalities/Hayakawas/hayakawas.html

- ↑ http://goldsea.com/Personalities/Hayakawas/hayakawas.html

- ↑ http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GSln=Hayakawa&GSfn=Sessue+&GSbyrel=all&GSdyrel=all&GSob=n&GRid=8710456&

- ↑ http://theeveningclass.blogspot.com/2007/08/silent-cinemathe-films-of-sessue.html

Documentary films[]

- 2006 - The Slanted Screen: Asian Men in Film and Television. Directed by Jeff Adachi.

Further reading[]

- Daisuke Miyao (2007), Sessue Hayakawa: Silent Cinema and Transnational Stardom, (ISBN 0822339692).